NGO Another Way (Stichting Bakens

Verzet), 1018 AM Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Edition 04: 26 March,

2009

(AUCUNE VERSION EN FRANÇAIS DISPONIBLE)

POLICY IMPLICATIONS OF AN INNOVATIVE MODEL FOR SELF-FINANCING ECOLOGICAL

SUSTAINABLE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT FOR THE WORLD’S POOR

By T.E.Manning*

A

model for self-financing ecological sustainable integrated development for the

world’s poor (referred to in the rest of this article as “the Model”) has been

presented. The Model is in the public domain. It can be downloaded from website

http://www.flowman.nl/, which is

controlled in the public interest by the Dutch NGO Stichting Bakens Verzet in

The

Model has far-reaching policy implications in many sectors. This paper

describes some of them. The Model weaves social, financial, service and

productive structures together into a single tightly-knit development fabric.

The fibres of the fabric are carefully interlinked, so there are several

possible ways of making an analysis of its effects on national and

international development policies. Anthropological, economic, financial,

political, social, and service- and production-oriented paths can all be

followed.

An anthropological approach is used for this particular paper. The

development of social groupings of humans, in particular over the last 11.000

years is used as the basis for the choice of administrative levels for project

applications under the Model. About 11.000 years ago, nomadic bands of dozens

of hunter-gatherers (mostly defined as “extended families” or “clans”) started

producing food and forming village groups. (Diamond J., Guns, germs, and

steel, Vintage, London, 1998).

Diamond refers to the village groups as “tribes” comprising several

extended families with an upper limit of “a few hundred” where “everyone knows

everyone else by name and relationships” (Ibid. p.271). Prof. Robin Dunbar of

Liverpool University suggests that the size of the human brain is linked to

social practices developed to bind small groups of 150+ members together. (Grooming,

gossip, and the evolution of language, Faber and Faber, London, 1996).

Even today, many rural villages, especially African villages, typically

have populations of “a few hundred” people. Even larger villages with

populations of a few thousand tend to be formed of clusters of smaller settlements each with “a few hundred”

inhabitants. (See detailed lists of villages for draft projects at website http://www.flowman.nl/, and in particular the

detailed population distribution maps for the Koulikoro project in

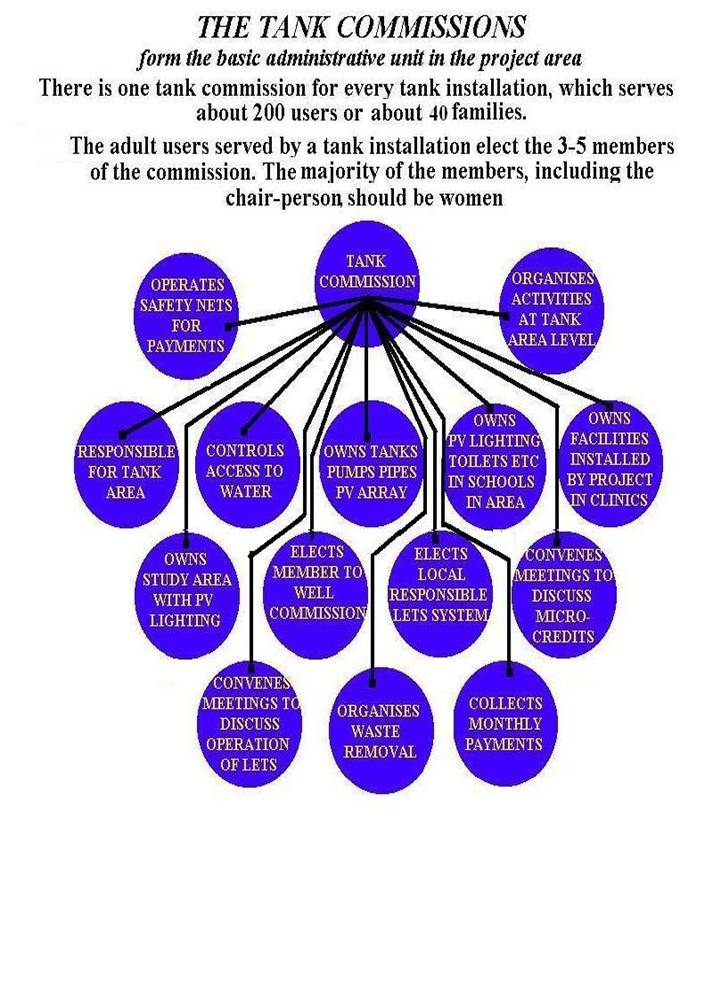

The basic administrative level used in the Model is usually called a tank commission. It can also be called a

local development commission. The tank commissions each represent 40-50

families grouped around a decentralised clean drinking water tank. The number

of people served by each tank is usually between 200-350. This corresponds to

Diamond’s “tribes” with an “upper limit of a few hundred”(op.cit.). The members

of the tank commissions are expected to be mostly women. Health clubs are first

set up in each tank commission area to make sure the women there can organise

themselves and participate actively in the election and administration

processes. The people in each tank commission area decide how many tank

commission members they want to choose. The commissions will usually have 3 –7

members. They have many important tasks.

They are the real hub of the many project structures. An active role for women

at this level goes a long way towards addressing the so-called “gender

problem”. Tank commissions also choose a representative to the intermediate

administrative level, called well commissions. These in turn choose central

committees at project management level. Women’s deep and direct involvement in

project planning, execution, and management is therefore actively promoted at

all project levels.

Figure 1 illustrates the main tasks of each tank (or local development)

commission:

(Fig. 1) The Tank Commissions

The

second, or intermediate, administrative level provided for in the Model is the

well commission. It can also be called

an area development commission. The well commissions are the equivalent of

Jared Diamond’s “chiefdoms” with “several thousand” inhabitants where “for any

person [living there] the vast majority of other people…. were neither closely

related by blood or marriage nor known

by name.” (op.cit. p.273). They developed some 7500 years ago as a result of

higher population densities made possible by the local cultivation of food.

Leadership institutions (“chiefdoms”) are believed to have evolved to create

ways of resolving conflicts naturally arising amongst inhabitants not directly

bound to each other by blood or marriage. Of special interest to integrated

development projects in the modern world is that the first systems for the

collection and re-distribution of wealth and the first forms of division of

labour were established in this phase. “The most distinctive economic features

of chiefdoms was their shift from reliance solely on the reciprocal exchanges

characteristics of bands and tribes……..[to] an additional new system termed a

redistributive economy.” (op.cit. p.275).

(Fig. 2) : The Well Commissions

The

well commissions provided for in the Model typically represent about 2000-2500

inhabitants. This population base supports some modern essential services, too.

A typical working area for general practitioners in industrialised countries is

1 doctor to 2000-2500 inhabitants. In the Netherlands this was 1 to 2347 on 1st

January 2006 (J.Muysken et al, Cijfers uit de registratie van huisartsen –

peiling 2006, Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL),

Utrecht, 2006.) Well commission areas can

also support a secondary education structure for pupils from the 2-4 primary

schools in their area. (Notes on education policies, below). Project structures

at this level include a transactions clearance structure for the local money

systems, and a structure for the manufacture of mini-briquettes for high

efficiency cooking stoves used in the area.

Each

well commission has a member nominated by each tank commission it serves. The

number of members will therefore vary from one commission to another, usually

between 5 and 9. Each well commission chooses intermediate level micro-credits

and local money transactions registration coordinators. It also chooses

representatives to the central structures management committee, and to the

central committees running the local money systems, the Cooperative Local

Development Fund, and where applicable, the Cooperative Health and Education

funds. As women are expected to have a majority at tank commission level, they

can be expected to nominate female representatives to the well commissions.

Women should therefore be well represented, usually with a majority, at this

intermediate level too.

The

third, or project level administrative structure provided in the Model

represents all 50.000-70.000 inhabitants living in a given project area. Jared

Diamond refers to this level as “states”, with “over

At

the same time, the population in the area must be large enough to offer a

market supporting specialisation of productive activities and services. It must

also be able to provide a variety of productive activities and services wide

enough to meet the basic needs for a

good quality of life for all in the project area. “We may thus define the

optimum number of the population [of an ideal state] as “the greatest

surveyable number required for achieving a life of self-sufficiency””

(Artistotle, Politics, Book VII, Chapter IV, tr. E. Barker , Oxford University

Press, London, 1948).

The

choice made in the Model in favour of local economy systems with an average of

50.000 to 70.000 inhabitants is therefore anything but new. However, there is

nothing critical or mystical in the number. Individual project areas may have

fewer or more inhabitants depending on population densities, and geographic,

cultural and ethnic aspects including language, and in particular on the

preferences expressed by the local population. Project areas in developing

countries today are seldom as densely populated as Greece at the time of the ancient City States. The population of

Greece is believed at that time to have reached 7-9 million (Dioxiadis,

op.cit.). Some project areas under the Model may therefore be larger than areas

covered by the Greek city states, especially where they include regional or

national nature reserves.

Third

level project management structures are formed by representatives nominated at

well commission level. They include central committees for any one or more

project structures, for the Cooperative Local Development Fund, for the Local

Money system, and where applicable, for Cooperative Health and Education Funds.

Since each well commission nominates a member to each central committee, the

number of members will vary from project to project, but will usually be about

35. The central committees, which can be viewed as “parliaments”, meet once a

year or more frequently if necessary. They choose management teams, which can

be viewed as “governments”. The management teams are expected to be small, with

3-7 members including administrative staff.

Each

of the three administrative levels described has its own clearly defined tasks,

including the election of those at the next level above that it will have to

answer to.

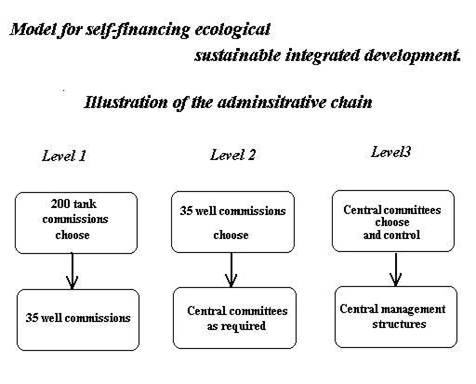

(Fig. 3) : The administrative chain

Each

project structure is managed via the three administrative levels described as

shown in Fig. 4.

(Fig.4) :

The administrative lines

Figure

5 gives a summary of common tasking at each of the three levels. The list is

not intended to be complete. The Model provides for the provision of basic

social, financial, productive and service structures necessary to a good

quality of life for all. The same structures also open the way to countless

other activities and initiatives which are as varied as the minds of those

conceiving them. No attempt is made even to imagine them.

(Fig.

5) : Tasking at each level

Model

for self-financing ecological sustainable integrated development.

|

Tank commissions. |

Well commissions. |

Project level. |

|

Health clubs/hygiene education. |

Management of well sites. |

Supervision and statistics. |

|

Drinking water.Drinking water. |

Water supply back-up. |

Maintenance & statistics. |

|

Family sanitation. |

Washing places. |

Training for housewives. |

|

Rainwater harvesting. |

Water sampling. |

Water testing. |

|

Local money assistants. |

Registration local money transactions |

Local money statistics, Inter-project relations. |

|

Collection of contributions. |

|

Conflict resolution. |

|

Collection of loan repayments. |

|

Conflict resolution. |

|

About 60% of micro-credit grants. |

About 25% of micro-credit grants. |

About 15% of grants. |

|

First-level social safety net. |

Second level social safety net. |

Project-level safety net. |

|

Production bio-mass for local use. |

Production of mini-briquettes. |

Statistics. |

|

Nurse |

Doctor. |

Local hsopital. |

|

Primary school. |

Secondary school. |

Trade schools, propadeuse for University. |

|

Lighting for study purposes. |

|

|

|

Radio-telephone communications (work for blind) |

|

Local radio station. |

|

Sports clubs. |

Intermediate facilities. |

Project level competition. |

|

Theatres, cultural groups. |

Physical Facilities. |

Cultural circuits. |

|

Personal food storage facility. |

Cooperative food storage. |

Export/import cooperatives. |

The Model

applies in principle both to poor urban and rural areas in both developing and

industrialised countries. However, preference is given to the execution of

pilot projects in rural areas in developing countries. (See further under

“Demographic Development Policies” below.)

Policy consequences

Project execution under the Model has many, far-reaching, policy

implications in many sectors and at all levels. At the same time, it must be stressed

that the Model does not claim to offer solutions to all the problems developing

countries face. Projects under the Model cannot act as substitutes for state

obligations. Some areas of activity mentioned below, such as curative health

and general education issues, are not directly addressed in the Model at all.

Other sectors, such as large-scale public works, defence and security, fall

outside the scope of local economic development and are not even mentioned

below. However, the Model provides for the creation of local social, financial,

service and productive structures. These structures can be used to promote the

gradual development of some services,

taken for granted in industrialised countries, that people in poor countries do

not even dare to dream of. Self-financed where necessary, and at a

surprisingly low cost. In those cases,

the following notes set out where they might want to go, and how they could get

there. It may take many years, even decades, for them to arrive.

In

short, the Model addresses some problems basic to a good quality of life for

all in the project area, and solves them

directly. It can contribute actively to

solving other problems over a longer term. Finally, there are some areas

outside local economic development where it has little or no direct influence

at all. Notwithstanding first

impressions some readers may have, the following descriptions are not

idealistic. The Model does not restate known development problems. It offers

concrete down-to-earth solutions to them. The paradigms and the concepts

presented are mostly so simple and obvious they should be viewed by most people

as an expression of plain common sense. The common sense of the ordinary man or

woman in the street. No university degrees are needed to understand them. None

were required to develop them. No special expertise is needed to put them into

practice. They enable the world’s poorest to design, execute, run, maintain and

pay for their own development within the framework of open, cooperative, interest-free,

inflation-free economic environments where genuine competition is free to

flourish

If the solutions to world-wide poverty alleviation issues really are so

simple, some readers may wonder why they have not been applied before. That is

a very good question. The answers to it go to the heart and the nature of the

currently dominating economic system. But they do not fall within the scope of

this paper.

Demographic development policies

Centralisation of power through the dumping of vast numbers of people in

mega-slums in unsustainable, uneconomic, ultra-vulnerable mega-cities in

developing countries is unnecessary,

foolish, and ethically unacceptable. In our times, it is politely called

“urbanisation”. Contrary to what we are sometimes led to believe, it is

relatively easy to control vast, poor, unorganised, disconnected, disinherited,

urban masses both individually and collectively deprived of any means of

providing for even their own most basic requirements. Civil disorder may

sometimes break out, but seldom has permanent effect. “Popular riot, insurrection, or

demonstration is an almost universal urban phenomenon, and as we now know, it

occurs even today in the affluent megalopolis of the developed world. On the

other hand the fear of such riot is intermittent. It may be taken for granted

as a fact of urban existence, as in most pre-industrial cities, or as the kind

of unrest which periodically flares up and subsides without producing any major

effect on the structure of power.” (E.J. Hobsbawm, Cities and insurrections,

Global Urban Development Magazine, vol.1, no.1, May 2005.) One of the purposes of the Model is to

counter this “urbanisation” by ensuring that people in rural areas attain a

good quality of life there with a full range of basic structures and services

and employment opportunities. Once a good quality of life in rural areas has

become reality, the Model can be applied in poor urban communities, where its

principles are just as effective. The Model is in principle applicable to poverty

alleviation in depressed rural and urban areas in industrialised countries as

well.

Empowerment of women

The important role played by women in structures at the three

administrative levels has already been described. The Model enables women to

play an active (leading) role in local development issues. They are

structurally freed from the drudgery of having to fetch water and firewood and,

with their children, from the dangers of smoke (air pollution in and around

their homes), water-borne diseases, and diet insufficiencies. Financial

structures such as local money system, interest-free micro-credits, and

cooperative buying groups put at their disposal greatly expand their freedom to

take productivity initiatives for which local and project level markets are

created. Their formal money budget possibilities are extended. They and their

children will have (with time) a better chance of structural medical care and

formal education, including hygiene education. They will all without exception

enjoy the benefits of drinking water, sanitation, and waste recycling

facilities.

Employment

and income

Tank

commission members, like all other persons active for the project, are fully paid for their work under the local

money systems set up as part of project execution. Self-financing sustainable

integrated development projects under the Model will usually have 200-250 tank

commission areas. This leads to the creation of 1000-2000 jobs some of which

will be full-time and others part-time according to the decisions independently

taken by the people living in each area.

Projects under the model typically create up to 4000 jobs and give

direct employment to about 10% of the adult population. The remaining 90% of

the adult population is free to use the local money and interest-free

micro-credit structures created by the project for the purposes of

productivity increase. At least Euro

Financial

policies

Projects

set up cooperative, interest-free, inflation-free, local financial

environments, within which private initiative and genuine competition are free

to flourish. Basic financial instruments created include local money systems

and interest-free cooperative micro-credit structures paid for and run by the

people themselves. These basic financial instruments can be supplemented as

required by self-financed self-terminating special purpose buying cooperatives

at tank commission, well commission and project level and by local

interest-free cooperative banking and insurance facilities. All formal money

financial structures are operated within the framework of the local money

systems set up, so not only are they interest-free, but the services are

usually supplied without any formal money cost to users as well. Formal money

costs for interest and services traditionally connected with financial products

are retained in the project areas. Local populations make small monthly formal

money contributions into their Cooperative Local Development Fund. These

contributions are used for multiple recycling in the form of interest-free

micro-credits for productivity purposes. The local financial environments

created during project execution operate in parallel and in harmony with

existing formal money structures. The local systems do not substitute the

formal money ones. Except for products and services provided for project

execution, users are always free to choose whether to conduct a transaction

under the local money systems or under the traditional formal money system. The

local money structures are all identically time-based. They interact with each

other to form a patchwork quilt of cooperative interlinked local economy

systems. Cooperation between systems is always on a zero balance basis, to

avoid all risk of financial leakage from one project area to another. (Model,

complete index, section 5.21 – Interest-free cooperative money structures);

(Model, complete index, section 5.22 – Interest-free cooperative

micro-credit structures). The network of powerful interlinked local economy

systems forms in turn a strong, independent, national economy in host countries.

Social

security policies

Few

developing countries are known for their efficient social security schemes in

support of the poor, the sick, the elderly and the handicapped. More often than

not, the sick have to pay in cash on the

spot for medical help. If they (or their families) are unable to pay, they

cannot get access to the services. In many countries, parents of schoolchildren

have to pay relatively high school fees and for school books and school

uniforms. Sometimes they even have to pay teachers’ wages where education

ministries fail to fulfil their duty to do so. This means that poorer families

are often unable to send their children, especially their daughters, to school.

Project applications under the Model can make a powerful contribution to social

solidarity in developing countries, as they set up a three-tiered social safety

network for the weakest members of society, both for their obligations under

the local money systems and for their formal money contributions to their formal

money Cooperative Local Development Fund.

Control

and ownership of local project structures

Management

and ownership of all tank commission level structures set up during project

execution are vested by the project in the “local tank commission for the time

being”. Physical service structures vested in them include drinking water and

lighting facilities and project structures provided in schools and clinics

situated in their tank commission area. The tank commissions also manage the

operation at tank commission level of the local money, interest-free

micro-credit and waste recycling systems set up during project execution. They are responsible for the collection of

the monthly contributions paid by each inhabitant into the Cooperative Local

Development Fund and for the operation of the social security or safety nets

set up for the poor, the sick, the aged, and the handicapped. They organise the

election of representatives to intermediate level (well-commission) structures

and of local money transaction specialists. Physical and administrative

structures run by the tank commissions can also be extended to activities in

the health and education sectors, as described below, and to interest-free

cooperative purchasing and investment initiatives. Similarly, intermediate

structures are vested by the project in the “well commission for the time

being”. Project-level structures are vested by the project in the “central

committee for the time being”. The social safety nets set up, together with

strong local social control and extended guarantee structures built into

micro-credit loan agreements should reduce defaults in the payment of

contributions. Default rates for loans made by Nobel Prize winner Muhammad

Yunus’s Grameen Bank were less than two

percent notwithstanding interest rates up to 18%. (M.Yunus, Banker to the Poor,

Public Affairs, New York 2003). Micro-credit loans under the Model are

interest-free and free from all formal money costs, as they are managed under

the local money systems set up.

Complementary

interests

A

qualifying feature of the activities of the tank commissions and of all other

structures set up under the Model is

that they fit in with, and operate in harmony and in parallel with existing

political, financial, and administrative structures. For instance, the local

money systems set up are operated in parallel with the existing formal money

system in the project’s host country. Except for transactions carried out for

the project itself, users are always free to choose whether to conduct a

transaction under the local money or the formal money system. Tank and well

commission members and management may also be members of statutory or voluntary

local development agencies or organisations. In some cases, the formation of

the tank commissions (independently of or together with intermediate and

project level structures) may be helpful in creating and running, free of

charge, local development organs foreseen in national legislation. For

instance, in the case of Togo, the Village Development Committees (CVD), which

are mostly inoperative and lack adequate finance, could be built into project

structures foreseen by the Model. The administration of the Togodogo Reserve

(Yoto District, Togo) can offer work opportunities to local people under the local

money system to help achieve sustainable management of the Reserve for which no

formal money funds are currently available.

Traditional

leadership and land ownership structures

Project

structures are not intended to interfere with the power and recognition of

traditional, elected and non-elected, institutions such as village heads,

chiefs, religious leaders, mayors, town councils, health boards, water boards,

tax department, police commissioners, or members of parliament. The tasks

carried out by the project structures

are all new ones, created by the people themselves (including mentioned local

leaders as individuals) within the framework of each integrated development

project. As the quality of life in each project area increases as a result of

project execution, the status of the traditional institutions is expected to

grow. For the tax department, for instance, a taxation base will be created

over time where none existed before. Traditional leaders are free to take

advantage of project structures for the management of communal property.

Management of communally owned tribal land and natural mineral and renewable

income resources can be brought free of

charge under the financial structures created by the project, so that costs and

benefits can be equitably distributed amongst the owner populations. For

instance, income from the sale of sustainably harvested wood from communally

owned forests or from the use by community members or nomads of communally

owned land for grazing can be distributed amongst the communal owners using the

financial instruments set up by the project. The cost of protecting natural resources such as flora and fauna can

be brought under the local money systems and divided amongst community members

to supplement the limited formal money resources available at national and

regional level.

Millennium

development goals

Project

applications under the Model provide complete structures for full, high quality

coverage for drinking water, sanitation,

waste recycling, smoke eradication and other services for 100% of the

population, without exclusion, in the project areas. The global formal money

cost does not exceed Euro 100 per inhabitant. Of this, 25% is provided directly

by the inhabitants themselves, in the form of work done for project execution

fully paid under the local money systems set up and “converted” into formal

money at the rate of Euro 3 per working day of eight hours. The remaining 75%

is initially supplied by external support agencies in the form of seed finance.

If the seed finance is in the form of a grant, monthly contributions paid by

inhabitants into their Cooperative Local Development Fund continue to be

recycled interest-free for micro-credits after the close of the first period of

ten years. If the seed finance is in the form of an interest-free ten year

loan, the contributions paid by inhabitants during the first period of ten

years are sufficient to repay the seed capital at the close of the first period

of ten years. The amount in the Cooperative Local Development Fund in that case

drops temporarily back towards zero. Since the inhabitants continue to make

their monthly contributions after seed loan repayment , the capital in the

Cooperative Local development Fund builds up again over the second period of

ten years to cover the cost of replacement of capital goods after twenty years.

The difference between a grant and an interest-free seed loan therefore becomes

operative only after ten years. In the first case, the flux of funds for

interest-free micro-credits is not interrupted; in the other the fund available

for micro-credits has to build up again during the second ten year cycle as it

did during the first one. Where part of seed funds is made available by way of

grant, the rest may be by way of soft (low interest) loans, including loans

from private sources. Condition for this is that the total sum to be repaid by

the population at the close of the first ten years’ period does not exceed the

total initial seed capital. On this

basis, a country such as Togo with a population of 4.500.000 can be “developed” by 2015 for a

total seed capital investment of Euro

337.500.000, some or all of which can be repaid by the local populations at the

close of the first ten years’ period.

Health

policies

The

Model addresses preventive medicine related issues by supplying health clubs

and hygiene education courses in schools, clean drinking water, sanitation

facilities, waste recycling, smoke elimination, better diets and drainage of

stagnant waters. While it is not intended to substitute for the duties of

national and regional governments with respect to remedial health care, it is

structured to help provide local supplementary services in some cases. Tank

commission areas (about 200 people) provide an ideal work terrain for a

qualified nurse. Suitable premises can be built under the local money systems

by the community for nurses willing to work within the local money structures

in so far as they do not receive formal money salaries. The cost of basic

equipment and materials can be cooperatively covered at tank commission, well

commission, or project level by small monthly formal money contributions paid

into a Cooperative Health Fund. The same considerations apply to structures for

doctors. Well commission areas each serving about 2000 inhabitants form an

ideal work terrain for doctors’ practices (J.Muysken et al, op.cit.) and for

other professions such as dentists and physiotherapists. Project areas with

50.000-70.000 inhabitants can support local hospitals, preferably at a central

point of the project area. Once the financial structures for cooperative local

economic development have been set up as a normal part of project execution,

basic health care structures can be provided at little or no extra cost to

financially hard-pressed government ministries. (Model, complete index,

section 5.62 - Health aspects). Project structures provide a natural

framework for middle- and long-term development in the health sector.

Education

policies

Some

improvements in education structures, like those for curative health care, can

also be covered under project applications. Single tank commission areas will

often be too small to support a primary

school on their own, as an ideal primary school population of perhaps

eighteen pupils for each grade is

required. (V. Wilson, Does small really make a difference?, Scottish

Council for Research and Education (SCRE) Report 107, Glasgow, 2002). Assuming six grades, a primary school

population of 120-150 would be needed. These requirements can be met by groups

of two or three tank commission areas working together. Simple locally

constructed, centrally located buildings (with clean drinking water,

eco-sanitation and photovoltaic lighting facilities) and locally built school

furniture can be supplied by the local populations under the local money

systems set up by the projects. Teachers, especially teachers originating in

the project area, willing to work within the local money structures can be paid

by the residents in so far as they do not receive (regular) formal money

salaries from education authorities. Similarly, well commission areas are

ideally sized to provide a secondary

education structure to pupils from the 2-4 primary schools in their area. With

classes of 18 pupils, they would need to have 350-450 pupils to provide

coverage for the various subjects studied. Project areas serving 50.000 to

70.000 are ideally sized to provide further education in trades and perhaps a

first year preparatory course (propedeuse) for university studies for which

students would subsequently need to go to larger centres. (Model, complete index, section 5.63

Education).

Policies

for sports and culture

The

financial and social structures set up under the Model make it possible for

individuals and groups to get cultural and sporting groups off the ground. The

Model does not attempt to list or regulate all of the initiatives which could

take place, as these are as varied as the minds and wishes of the people. They

include sports, coaching and training activities in general, theatre, music,

local arts and folklore groups. Basic facilities can be provided under a

combination of the local money systems and interest-free micro-credit

structures. Sports competitions can be organised amongst clubs in a given

project area, and amongst inter-linked project areas. Cultural circuits can be

formed, almost “automatically”, for theatre, dance and music groups, providing

them in many cases with full time work.

Energy, environment and conservation policies

All initiatives taken under the Model are directed towards zero net

energy use, so as to avoid financial leakage from project areas and wastage of

resources. Energy used must be in the form of renewable energy originating in

the project areas themselves, so that they can be produced and paid for under

the local money systems set up. By way of example, the distributed drinking

water systems are powered by solar photovoltaic panels. Locally produced

high-efficiency stoves are fuelled by locally produced mini-briquettes made

from locally grown crops and waste products. Public transport facilities may be

driven by bio-fuels produced locally on a small scale. Local production is necessarily

environmentally neutral and is always intended in the first place for local

consumption. Communities in project areas usually request cooperative food

storage facilities coupled with traditional food conservation practices such as

solar drying and storage in the form of edible oils. National level and

regional environmental and conservation

agencies can receive job-creating support from the local money systems. An

example is the protection and sustainable exploitation of the Togodo National

Reserve already described above, where the Reserve could participate as a

member of the local money system, and use the services of local inhabitants as

wardens and for forest maintenance and services in exchange for sustainable low

level local exploitation of timber, hunting and fishing rights. (Model, Yoto

Nord-Est 10 project).

*The author

Terry Manning is a 64 year old New Zealand lawyer. Resident in Italy for

25 years, he was involved with the

development of innovative pumping technologies for the world’s poor and in

particular the spring rebound inertia hand pump technology and the solar

submersible horizontal axis piston pump technology. For family reasons, he has

been living in the Netherlands since 1993. His observations of the world of

development (“the aid industry”) were such that he decided it had to be

possible for even the poorest to self-finance their own basic integrated

development. After many years’

self-financed work, he succeeded in moulding an original combination of social,

financial, productive and service instruments into a Model for self-financing

ecological sustainable integrated development suitable for general application

in rural and poor urban areas throughout the world. The Model enables

interested parties to draft their own integrated development projects free of

charge and to apply for seed financing for them.

Terry Manning has placed his work in the public domain, under the

control of the Dutch NGO “Stichting Bakens Verzet” which means “Another way”.

His address is Schoener 50, 1771 ED Wieringerwerf, Netherlands, tel.

0031-227-604128l; e-mail: bakensverzet@xs4all.nl

NEW HORIZONS FOR DEVELOPMENT: SOME SHORT POWERPOINT PRESENTATIONS

MORE ON SOME BASIC ISSUES COVERED BY THE MODEL: